Sharing his atmospheric and intimate latest record Croak Dream, the Atlanta-based British musician talks about life, death and why his albums are chronically shy.

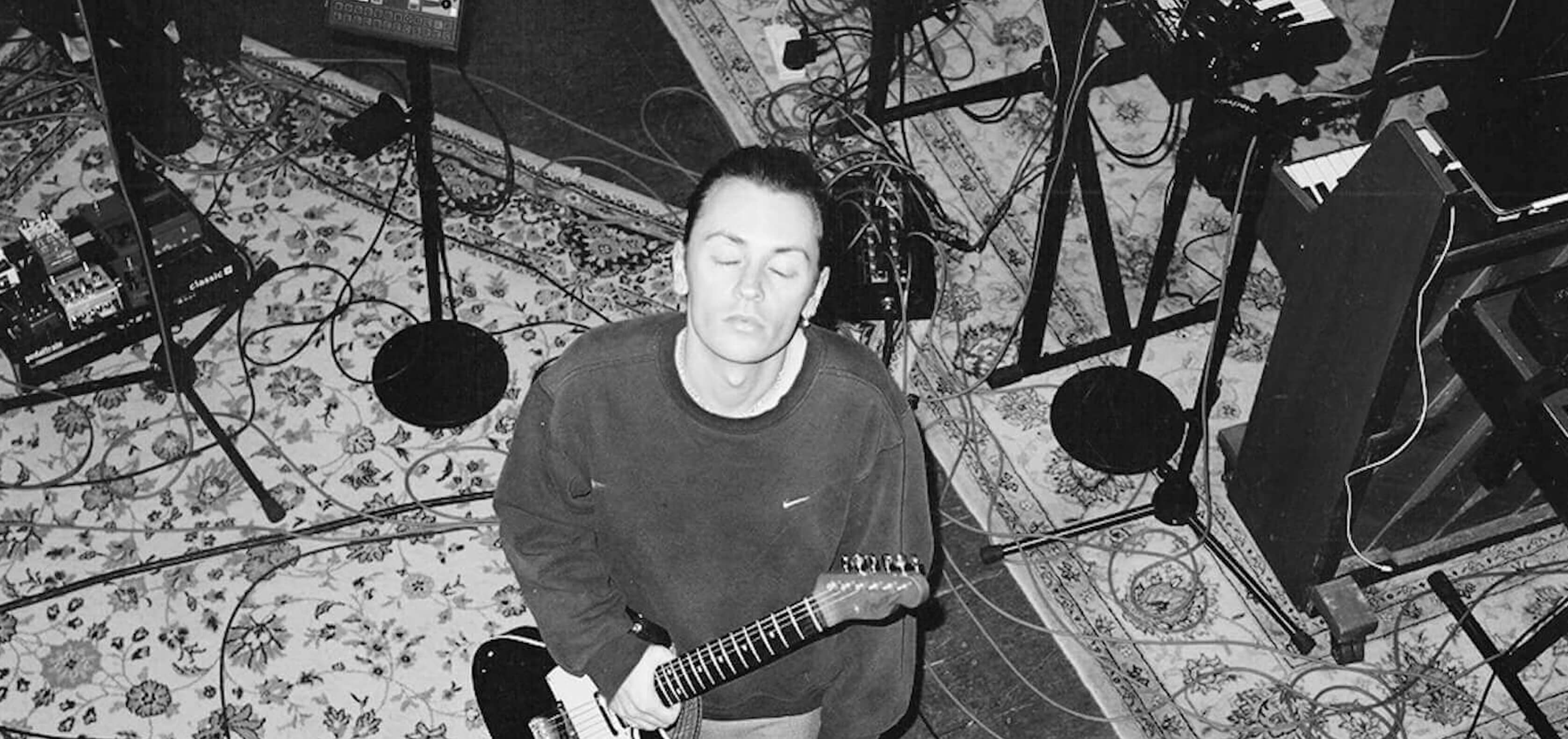

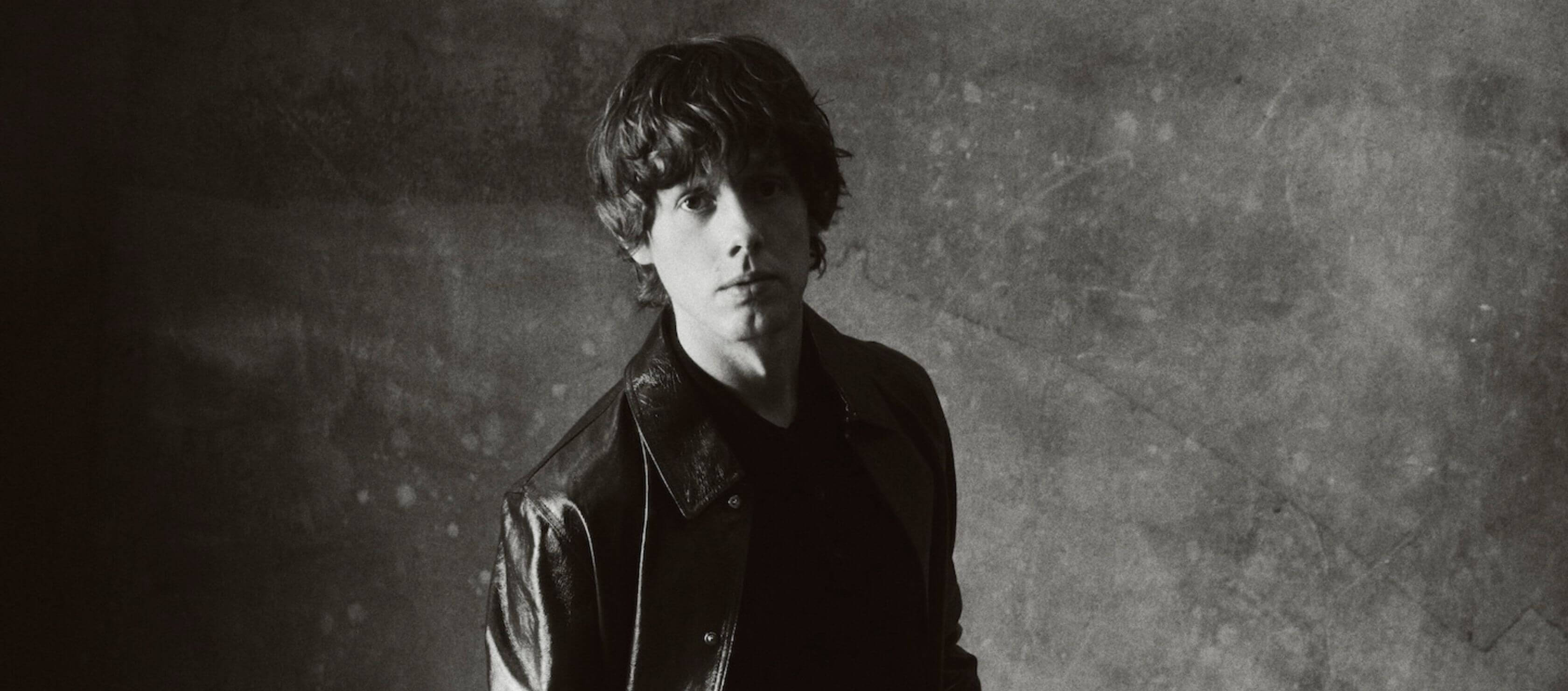

Few musicians hold intimacy in the palm of their hands as well as Puma Blue. The South London-raised multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and producer – aka Jacob Allen – has been refining his sensuous brand of hazy, jazz-infused music since 2017. Now living in Atlanta with his fiancée, his popularity has expanded well beyond his local orbit since then, having released multiple bodies of work and toured all corners of the world over the last near-decade.

His third full album, Croak Dream, is a rebirth of sorts for Allen. Whilst touring extensively in 2023, he experienced challenging bouts of depression. This prompted him to go into therapy, and later release two stripped-back, lowkey projects last year (antichamber & extchamber), which saw him return to his solitary songwriting roots in their purest form.

Croak Dream builds beyond this. For a songwriter who’s renowned for being vulnerable, it’s only here that Puma Blue feels he’s finally been able to open up to his fullest potential. He also delves into new, spontaneous sonic terrain through the valuable influence of the album’s co-producer, Sam Petts-Davies, who saw them cut up and fragment their straight-to-tape recordings at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios into unique, idiosyncratic assortments. By banishing second-guessing and fully letting go, Puma Blue reaches new heights on Croak Dream.

Man About Town meet Puma Blue fresh from the album’s release ahead of his in-store show at Rough Trade East in London, to talk about life, death and how making music is a lot like dating.

Photography by Liv Hamilton

How has 2026 treated you so far?

Honestly, it’s been a really hard year already. In the space of a month, I’ve been to two family funerals and then buried one of my cats. It’s been intense. I lost my uncle, then my 102-year-old great-grandma died. I can’t believe my grandma, who is nearly 80, went to her mum’s funeral at that age, which was wild, but also kind of sweet. Some people, it’s less like you’re grieving their loss and it’s more like a transition into some sort of other plane.

How has living in Atlanta for the last five years compared to London?

The pace is different – that’s the biggest thing. I feel like in London, there’s something about it that’s like living in a cardboard box of cement and coffee and trains, whereas in Atlanta, it’s a green place, so I feel a lot more connected with nature out there. No one can make a good cup of tea in America, though. I hate to say that, but the Americans don’t know what they’re doing. I miss my friends back home, I miss my family, and the amount of socialising is on another level in London. I also miss British telly quite a bit.

Congratulations on your album release. How does it feel to have it out in the world?

It feels like another day, really. I couldn’t say that before with previous releases. I used to get worked up around release time. If the music was doing less than expected, it would get under my skin, and I would reflect upon how I felt about myself. But I’ve been working so hard on my personal life and mental health over the last couple of years, and I’ve noticed this time around with this album release that I’m feeling a sense of peace. It feels like a collection of old stories that everyone now has access to.

I read that you dealt with a bout of depression whilst touring your last album, Holy Waters. Were there any points during this time when you felt a sense of disconnect from your work?

This is a hard question… No, is my honest answer. Music is always something I can connect to. There are times when I’ve been so grateful for it, because it feels like the only friend I can talk to. I feel like I’ve let music down a hundred times with my relationship to it, how honest I’m being, or whether I’m honouring it properly. But it has never let me down.

Have you found it harder or easier to make music as time has gone on?

Easier. I spent so much of my 20s second-guessing what the audience wanted, and what fit under the Puma Blue umbrella. It’s like being on a date; you have to put yourself across as succinctly as possible so that someone knows if you’re a match or not. Once you’re seven years into a relationship, though, you’re learning the weirdest shit about each other. You learn each other’s quirks, and you’re getting into the beautiful uniqueness of being a human being. It’s the same with music. On this new album, I feel like I’m able to brandish parts of me that I was scared didn’t make sense before, and now I’m just like f**k it.

Tell me more about the central theme of Croak Dream. What questions did you ask yourself to approach this project? And what emotions did they bring up?

I feel like my albums have been chronically shy. As an artist, you kind of are your music in a lot of ways. Through going to therapy, I’m seeing that there’s a lot I hold back or hold in, which is ironic, because I’ve been praised by people for being vulnerable and open, but I think that’s only half true. There’s so much that I’ve been keeping back or dimming. So, when I was making Croak Dream, I thought, ‘What if I had more fun and was a bit more reckless?’ I applied this same philosophy to the lyrics, themes, guitar playing… everything we could make more fun or more weird. The less safe I played it, the more fun I had. This all fed into the record’s central theme: ‘If you knew how and when you were going to die, how would it change how you decided to live?’ It feels morbid to me to avoid the subject of death, but that’s not what the album is about. To me, it’s about life.

I feel like you’ve always been an artist who utilises music as a means of catharsis. Were there any lessons that you learned about yourself while writing these latest songs?

It can be easier to fall into the trap of going through the motions. Especially since most artists don’t earn a ton of money in music, there’s a lot of pressure to follow up your last album with something ‘better’. But what does that mean? That’s such a vague way to think about music. After Holy Waters, the most economical thing to do would’ve been to make a new indie pop record, but that would’ve felt so insincere for me. The only thing I’ve got is how honest I can be at any given time. There’s got to be someone else in the world who will benefit from me choosing to go this way, almost like a message in a bottle, you know? Music is more like a spiritual practice to me. I’m just going to try staying on the path of what feels real.

I first discovered you through your 2017 debut EP, “Swum Baby”. With Croak Dream, stylistically, did you feel a need to revisit this EP’s solitary songwriting roots?

I did, but not for anyone other than me. It reignited the love I had for a lot of the music that I used to listen to. I haven’t listened to much jazz music over the last few years, but back then I was listening to it all the time. I’ve gone back to some African music, weird classical stuff, hip hop, jungle and dub music. I felt like I’d been here before, but now I’m older and appreciating new things about it all, and I saw the same music from a different perspective. It was fun.

The title track is a stand-out. It feels like something from Radiohead’s Kid A…

Referencing Kid A warms my heart. I’ve heard some Radiohead comparisons from people with this latest album, especially working with [Thom Yorke collaborator] Sam Petts-Davies, which makes me worry that I’m making derivative work. But with Kid A, what I like about that album is there’s so much variety on it. I love how much they explored. And I guess that’s what we were trying to do, by making something that bounced around like a tennis ball and hit lots of different spots.

Apparently, the track’s lyrics centre around laying the ghost of a person you’ve had nightmares about to bed.

There’s someone from my past; despite not having seen them for over 10 years, they pop into my subconscious all the time. I still have dreams about them, and I’m working on them. But this song was almost an attempt to exorcise that demon, tying in with the ethos of the album, thinking, ‘Why don’t I just do this?’ There was a new catharsis there for me by facing it.

“Hush” could easily sit on Dummy from Portishead. You describe this as your version of a Puma Blue-style James Bond theme?

I’ve gotten really into trying to be bored like I was before I had a phone. If I’m stuck doing nothing, I’m making a conscious effort to read books, shuffle cards, play solitaire or whatever. This was something I did when I was staying in a hotel room last year. I wasn’t in the mood to write something ‘serious’, so I thought I’d try and write a James Bond-style song. It’s funny what ends up making a good song and what doesn’t; sometimes you can try and make something honest and sincere, and it turns out rubbish. This one started as kind of a joke, but it quickly turned into one of the more intense songs on the album.

What are you most proud of with Croak Dream?

I guess I’m proud of how ‘me’ it feels. All my albums have sounded like me, but this one feels the most naked. I’m leaning into all my influences and wearing them on my sleeve, and it feels like the first time I’ve been proud of that. Maybe that’s coming with age, too. I turned 31 recently and don’t want to spend my time masking as I did in my 20s – I’d rather get weird or geeky with my music and be proud of that. I’m proud of the artwork as well. My fiancée, Liv, and one of our best friends collaborated on it, and they absolutely nailed the vision.

I read in a previous interview that your fiancée once described you as ‘the first person to lighten the mood, but also the first to take it to a really deep place’. Do you feel like this duality is something that’s still inherent in both your personal and artistic self?

Yeah, that’s spot on. God, she knows me so well! I love Park Chan Wook, the director. I love how he’s able to make things so tender and romantic, but also funny and horrifying. I wanted the band in the studio and the audience listening to squirm with the giggles and find seriousness in the darkness of this record. I like that idea of contrasting.

What’s next on the horizon for Puma Blue?

Obviously, the album is out now, we have a tour coming up too, and then I may be an independent artist for the first time since my debut EP, unless we re-sign with the label, which is a possibility. I guess I’m wondering how to keep this energy going in terms of writing stuff that feels true to me. I’d like to keep pushing the envelope of what Puma Blue could be. I’m also getting married next year. That’s the big news!

![Picture of “When We Were Developing Series [2], We Were Very Conscious Of The Live Debate About What It Means To Be British”: Tom Hiddleston On The Night Manager’s 2020s Comeback](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F02%2Fdigsfo.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_CWFdNAdeZh3XprRwbBCr67w5FLBF)

![Picture of “[The Bridgerton Press Tour] Is Like Being On Some Sort Of Hallucinogenic Drug”: Luke Thompson Is Next In Line](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fadmin.manabouttown.tv%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2026%2F01%2FLUKE-THOMPSON-hero.jpg&w=3840&q=85&dpl=dpl_CWFdNAdeZh3XprRwbBCr67w5FLBF)